posted 07-26-2009 02:56 PM

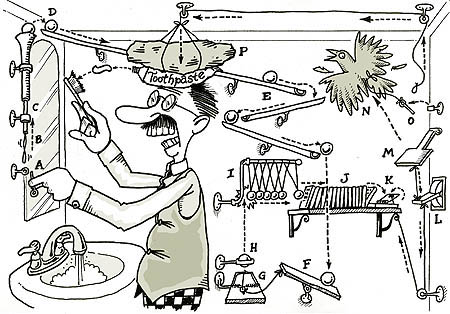

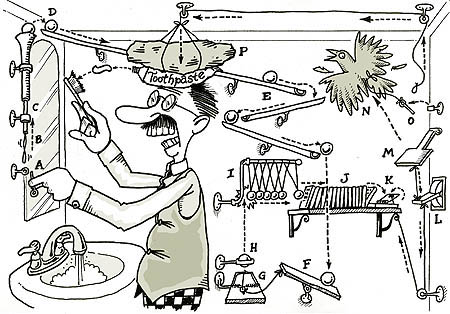

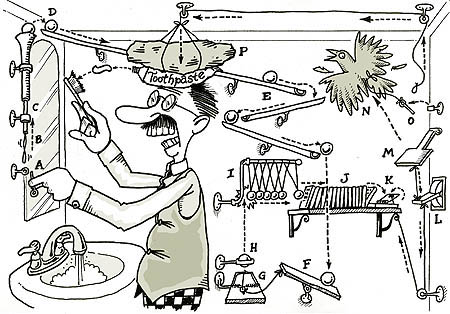

Your therapist is asking for a convoluted logical mousetrap or linguistic rube-goldberg exercize.

The suggestion is to ask the offender whether he "is" lying (to you) when he admitt(ed) to..."

Presumably, he will answer "YES," meaning that if he passes he is telling the truth when he says that he was lying when he made those admission. Which, by inference, means that he was not lying when he was previously denying those acts, which, by further inference, means he was telling the truth all along. Poor guy was just misunderstood by those suspicious and unfair professionals.

Of course, if he fails, while answering "yes" to questions about lying when he made those admission, they would infer that he is lying now, and was not lying when he made those admissions, and that tells us that he was lying when he was previously denying those acts.

This is now a treatment issue.

Problem is the therapist (who is hoping all this fancy-schmancy logical hoola-hooping will somehow solve his problem with the guy), may not know how to properly filet this guy in the context of the therapy group.

If he comes in for another polygraph, you should take his money, and ask him the exact same questions.

"Did you do it?"

If he says 'no' then run the test and take it from there.

If he folds again and says 'yes' then do the same thing as before. Get the confession on tape, have him call the tx provider and PO.

Then...

Lather.

Rinse.

Repeat.

You'll eventually wear him out.

Or, he'll succeed at wearing out his team, and will succeed at turning the polygraph and containment process into an excercize in silliness and nonsense - which is probably what he's actually hoping for. Just stir up enough frustration and chaos that the professionals do silly things, then make an issue out of that if you get revocated.

There is a reason we call it a lie detector test, and not a truth detector test.

It is much easier to account epistemologically for what exactly we mean when we say someone is lying, compared with what it means when we say someone is telling the truth.

Philosophers have been attempting for a long long time, without great success, to define what it means to say that someone or something is truthful, and what types of things can be true. The second part is much easier than the first - statements about things and events can be true. The first part is much more difficult. It is massively complicated by associated problems related to the depth and breadth of factual knowledge regarding a thing or event, and the related problem that there is always more detail and more information regarding said thing or event. If truth means leaving nothing out, or complete truthfulness (which is circular), then passing the test would allow us to assume we then know "everything" about the thing or event which is impossible.

Let's not pretend - it won't impress our detractors, and will only fuel our opponents.

To the extent that we think the polygraph measures lies, per se, then we'll be tempted to ask about things like "lying" in test questions.

Polygraph, like every other test, simply measures reactions to a stimulus - which describes a behavioral act for which we are concerned about the examinee's possible involvement. The best stimulus is a description of the behavioral act of concern. Questions about lying are rather indirect. Why not stimulate the issue directly.

Questions about "Lying to me" (the examiner) are not correct in terms of good testing science because they turn the examiner from a neutral test administrator into the test stimulus. Do we really want to encourage the notion that the examinee reacts to the examiner? Probably not. To do so gives every examinee an excuse for not passing - they were reacting to the examiner, not the question. There is zero empirical support for this type of question, and questionable face validity.

In fairness, there may be times when an indirect approach to questioning is warranted. I will argue that "did you lie about" has better face validity than "did you lie to me about..." because it does not get the examiner's ego and personality mixed up with the test stimulus question.

We will be better off if we stick to the basic idea that the question, which describes the examinee's behavior, is the stimulus - which is simply presented by the examiner. If they react to the stimulus, then we want our argument to be grounded solidly on the premise that they reacted to the stimulus issue, not the examiner, because they were involved in the behavior.

The APA PCSOT Model Policy does not endorse confirmatory testing. See section 5.5 which states:

quote:

5.5. Confirmatory testing. PCSOT activities should be limited to the

Psychophysiological Detection of Deception (PDD). Confirmatory testing

approaches involving attempts to verify truthfulness of partial or complete

statements made subsequent to the issue of concern should not be utilized in

PCOST programs. Truthfulness should only be inferred when it is determined that

the examinee has not attempted to engage in deception regarding the investigation

targets.

It will be quite unwise for us to try to get into the business of verifying truthfulness (which means "complete truthfulness") for sex offender's statements.

There is always more information.

The only way there is not more information is if the offender exaggerates. The problem then is that we then empower the offender as the offender as the victim of an unfair and arbitrary system that forces him to make false-admissions (exaggerations) in order to pacify the unreasonable professionals who want to pretend they can somehow know everything he ever did to someone.

Don't try winning that argument in court.

Instead truthfulness is simply inferred when it is reasonably verified that he is not lying when answering 'no' to a simply and behaviorally descriptive question. Sure, there is more. There always is. Sure, there are times when learning "more" adds incremental validity to our decisions. There are also times when we know enough that adding "more" doesn't add any incremental validity to our decisions.

Remember that this is a PCSOT exam.

Government and police agencies may have different rules, and may need to have different rules - because they may sometimes have to evaluate the credibility of an information source or informant. For a gummit or police agency, dealing with whether or not to utilize or take action on information gained from persons of questionable credibility, there may be no better alternative than to attempt to conduct a "confirmatory" test regarding the examinee's truthfulness. To neglect that might be to neglect the opportunity to have a needed conversation with the guy.

Engaging in confirmatory testing in a PCSOT program will only prompt the bleeding heart do-gooders to want to use the test in a less perjorative way than the present lie-detector approach - which will only set the stage for some painful experience when we later learn we had been duped when we were lead to believe we knew everything there was to know - because he was truthful.

In a lie-detection context, sure there are still errors, but the same pretense isn't present. We can say with some level of empirical confidence that someone isn't lying about a particular narrowly focused questions, but that doesn't mean he's completely truthful about everything.

.02

r

------------------

"Gentlemen, you can't fight in here. This is the war room."

--(Stanley Kubrick/Peter Sellers - Dr. Strangelove, 1964)

Polygraph Place Bulletin Board

Polygraph Place Bulletin Board

Professional Issues - Private Forum for Examiners ONLY

Professional Issues - Private Forum for Examiners ONLY

Post admission testing

Post admission testing